A Peek Inside America’s Most Dazzling Menu Collection

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE JULY 29, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

If you spent any time on the website formerly known as Twitter in the last few months, you may have seen a vintage menu going viral.

The menu, dated to February 17, 1941, is from the Warner Bros. Studio Cafe in Burbank, California. What made it so fascinating was the sheer amount of food and the number of midcentury oddities on offer. The hungry starlet or sound technician, if their wallets allowed, could start with imported caviar, follow it up with a T-bone steak, and finish their meal with a glass of half-and-half.

It’s incredible how many details about the era jump off a single page. One of the daily specials was “hot dogs with Liberty cabbage and carrots.” Liberty cabbage was sauerkraut, temporarily renamed during a wartime rejection of all things German. Another special, a “Fresh Vegetable Dinner” with a poached egg, is a plant-based exception on an otherwise very meaty bill of fare.

As it happens, this document belongs to Henry Voigt, the premier collector of historical American menus. Recently, part of his collection went on display at the Grolier Club in New York, which was accompanied by a profile in The New Yorker. Voigt started his menu collection after nearly four decades working for DuPont and runs a blog about his hobby called The American Menu.

Gastro Obscura sat down for an interview with Voigt, touching on American menus, how going out to eat has changed since the 19th century, and how, unknown to him, one of his menus became a hot topic. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q&A With Henry Voigt

How did you start collecting menus?

I started towards the end of the 1990s, with online auction [sites] like eBay and others. The online auctions are very efficient and low cost.

Why menus?

I’ve always been interested in food and wine. And I’ve always been interested in the history of everyday life. American historians haven’t focused quite as much on everyday life as some of the European countries. We just need a curated [menu] collection in this country.

What’s the date range of your menus?

It starts in the 1840s, because that’s when the story starts with regard to menus in the United States.

There are menus that predate that, but they’re few and far between, and they come from things like Lafayette’s visit in 1824 and so forth. We weren’t an urban country. We weren’t yet a wealthy country. So it was in the 1840s when the story first started for us.

And it started with table d’hôte menus, at hotels, for the most part. New York City had restaurants, like Delmonico’s and such. But the story really starts with hotels at the very beginning. I start there, and I end yesterday! [Laughs]

Are any regions particularly well represented?

It’s geographically very diverse, but, as Tennessee Williams once said, the United States has three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everything else is Cleveland. And I think when you collect menus, that’s kind of the story. I would add Los Angeles to that, because it’s always been an eating-out town.

My collection is strong in New York material, San Francisco material, strong in 19th-century material—which is very important because that’s a lot of what was lost and not replaceable.

By “lost and not replaceable,” do you mean that the foods on there are extinct?

No, the menus themselves are gone. But the foods are all different too. We don’t eat the same foods.

There are things on these menus that I’ve never seen in a modern restaurant.

That’s correct. And a lot of that is because the species were wiped out, or loss of habitat wiped out the species.

The big game dinners in the autumn, which were an American tradition at some hotels like the Grand Pacific in Chicago, were national news. They would procure four or five dozen different species of birds and animals of all kinds for those big banquets. That was the abundance of America, and distinguished the American culinary scene from Europe.

Certain foods were symbolic of class. For example, canvasback ducks or diamondback terrapins from the Chesapeake Bay were de rigueur in the upper classes for special events. Foods that denote class have changed.

How many menus do you have on hand now?

I’ve used the number of about 10,000. I haven’t actually counted them and it might fall short of that, but not by much.

What’s a highlight of your collection?

This was a women’s restaurant in New York, and it was quite a thing in antebellum New York: Taylor’s Saloon. It was called saloon, meaning just “large restaurant.” Spaces were made respectable for women by going over the top with the ornamentation. And Taylor’s was no exception to that. So they had high ceilings that were frescoed and Corinthian columns painted red with gilded edges and bubbling fountains and large mirrors and black walnut tables. It was quite a place.

Europeans were just astounded by this. Women gallivanting on their own, meeting with friends, having lunch. “My God, what’s the world coming to?”

The menu is just not like anything you’ve ever seen. It’s 58 pages. It has gutta-percha covers inlaid with mother-of-pearl chromolithographic borders around each page. And on the recto of each leaf, there’s part of the menu, and on the verso of each page, there’s an advertisement.

One of the advertisements is from the El Aliso vineyard in Los Angeles. This is before the Civil War, and there was no transcontinental railroad. Those things had to be shipped [13,000 nautical miles] around the Horn.

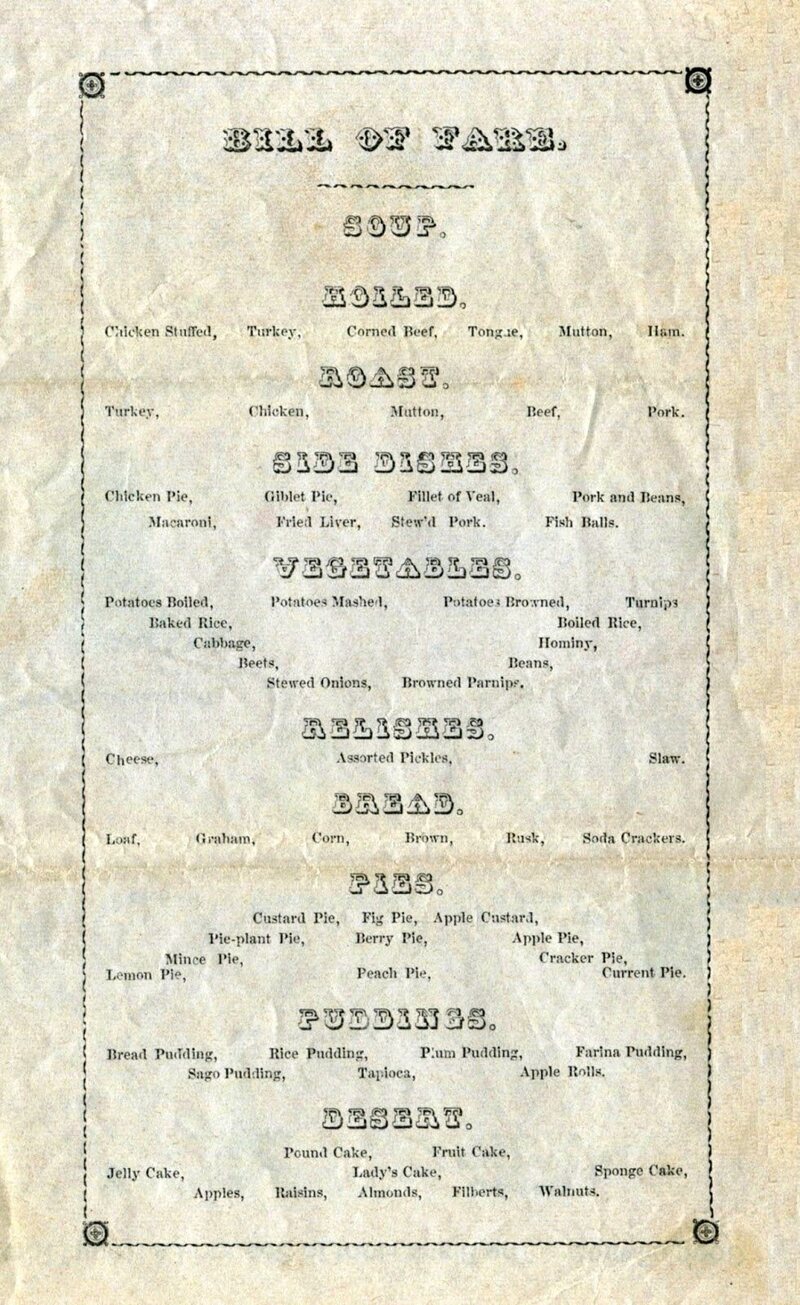

Something that’s always fascinated me about these old menus is that they always had so many dishes on them, way more than modern restaurants. Were all of those things always available

We don’t know! I don’t think so. I think people understood that, when they were dining, that there weren’t 12 different boiled meats actually available that day.

They would probably have to ask the waiter.

And the waiter would say “No, we’re out.” Now, if you’re talking about the Astor House in New York or Burnet House in Cincinnati, yeah, they had this stuff. But that was the reputation of the house. And the menu, it was more than that.

How so?

I have a nice menu from the early 1880s, from a young man who had left home in Connecticut and had gone to El Paso, Texas, of all places. And he wrote his parents that he had arrived safely, and he enclosed the menu that he had that night for dinner at the local hotel.

The menu itself was symbolic of a couple of things. One was, this place isn’t completely uncivilized. And also, the menu enclosed with the letter sent another message, which was, “I’m okay.”

You look at menus coming back from the front. The military goes to great lengths to actually provide a menu and traditional foods on the holidays, in some of the most horrendous conditions.

Soldiers would fold the menu up and send it back with a letter. “I’m okay, look at this.” The symbolism of food—I think people underestimate it. It was not just something that represented American values and American civilization, but it also represented reassurance. “Don’t worry about me, Mom. I’m okay.”

Speaking of long menus, a menu from your collection went viral on Twitter earlier this year.

Huh?

I wondered if you had seen that. It’s the Warner Bros. Studio Cafe menu from February 17, 1941. It has tens of thousands of likes and retweets. I’ll send you the link.

Oh yeah, do, because I had no idea! [Laughs]